Is “recency” even a word? Not in most dictionaries it isn’t. You’ll get sent back to the tray if you try to play it in scrabble or its popular online equivalent, Words With Friends.

Yet the word works very well to describe one of the must‐know biases that affect the way we think in pursuing rewards and avoiding pain, as we do in investing. Behavioral Economists, those deep‐thinking scientists who help us understand why we exercise bad financial behavior when we know better, have coined “recency” to describe our tendency to put more weight than we should on recent events.

And what is the cost for falling prey to our recency bias? According to the QAIB1 study from Dalbar, investors underperform by 3‐6% percent PER YEAR due to our hard wired emotional makeup. In some cases this can make the difference between sustaining and depleting wealth.

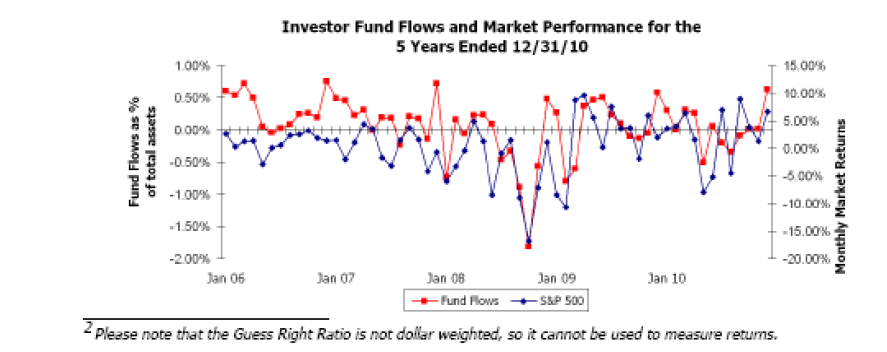

A clear example of the recency bias causing exuberance was the heyday of tech investing, the late 1990’s. Do you remember that time? Every advisor remembers vividly the discussions we had, struggling to talk clients out of making huge bets on technology stocks that everyone “knew” could only go up. For a reminder of how that worked out, look up the stock performance of prior superstars like Dell Computer, WorldCom, Juniper Networks, Nortel … the list goes on. Ditto for how most people felt about real estate prior to 2006. It is common to quote Warren Buffet who says he likes to buy when others are fearful and sell when others are greedy. The Dalbar1 chart below paints a different picture, showing how funds flowed into and out of stock market mutual funds almost lockstep with the monthly returns of the US Stock Market over a five year period ending December 31, 2010.

It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to agree that the news right now is pretty bad. Congressional approval is at an all time low, Europe struggles with massive debt issues, the Middle East is erupting into a new social order and the US stock market is at the same level it was 12 years ago in 1999! There have been periods in the past when the stock market was flat or down for a dozen years at a time, but those born after World War II (baby boomers) became accustomed to unusually low volatility and rising stock prices pretty consistently since 1981. That coincides with boomers buying houses and saving for college educations and retirements and it all seemed pretty much on track until the year 2000. Having to deal with the return of volatility and uncertainty in more historically common amounts has been a big adjustment, to say the least. Hence our title, “The Mother of All Recency Biases”.

Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist for Charles Schwab, reported at Schwab Impact Conference this year that 40% of Baby Boomers when polled respond that they have sworn off stock market investing forever.

The recency of the bad news has caused investors to pull their money out of stock mutual funds this year like water through a broken dam. In the past this has usually signaled a good time to buy, not sell. Similar sentiments were common after the last deep and enduring bear market of 1973‐1974, but stock ownership increased in ensuing years as returns turned positive once again. The Dow Jones Industrial Average finished 1974 at 616, and has risen over 18 times since then, to about 11,500 as of this writing.

How do we deal with the recency bias‐ or our other human biases for that matter? A good place to start is to make a distinction between how we feel and what we think. A negative return over any period of time (a day, a week, a decade) can trigger feelings of scarcity and deprivation. The feelings are real but alone they have no practical effect. Feelings represent how we think about facts. We can choose to acknowledge the feelings, recognize them for what they are, then set them aside in order to make a more measured decision.

This has been an atypically poor decade for holders of large US common stocks. Diversification into bonds, small and value stocks has improved returns substantially over the past 10‐12 years, but volatility has stung across all growth asset classes and the result has been risk fatigue. That means we’re feeling tired from all the ups and downs. Meanwhile we should remember that our economy (Gross Domestic Product or GDP) has grown, from just over $10 trillion to almost $14 trillion since 1999 and the world economy has expanded even more. US Corporate profits are more than double what they were in 1999. Interest rates are punishingly low for holders of “safe” government bonds and bank deposits. A balanced and diversified approach has proven itself during a challenging decade and is the best antidote for the emotions triggered by our recency bias.

1. QAIB – Qualitative Analysis of Investor Beharvior, Dalbar, Inc. Research and Communications Division, March 2011, page 9